President McKinley, whose popularity was heightened by the victory of the United States in the Spanish-American war, was easily returned to a second term in the election of 1900. His running mate was Theodore Roosevelt, Governor of New York. In less than a year McKinley’s presidency was cut short by an assassin’s bullet delivered in Buffalo, New York. “Now that damned cowboy is in the White House!” declared political boss and Senator from Ohio, Mark Hanna on hearing the news.

|

| President McKinley Reviews Troops, September 6, 1901 |

In September 1901 the President scheduled a visit to the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, NY. Planning for this extravaganza had been in the works for years but postponed during the Spanish-American War. With the war’s conclusion the preparations for the Exposition could go forward and all the governments of the western hemisphere were invited to attend. It occupied 350 acres with buildings whose architecture reflected the style of the Spanish Renaissance. The major theme of the exposition extolled the wonders of the new source of power – electricity.

Arriving on September 6, President McKinley welcomed visitors at the Exposition’s stadium followed by a short reception at the Temple of Music. Noting that the reception was to last only ten minutes, an aide felt the president was unnecessarily exposing himself to danger. In reply, the president commented “No one would wish to hurt me.”

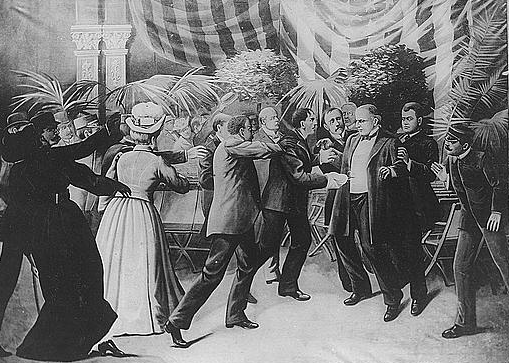

McKinley stood at the head of the reception line in the Temple of Music. His famous handshake whisked each recipient on his way. A slim, 28-year-old man named Leon Czolgosz approached. He had a handkerchief wrapped about his right hand. As the president reached for his left hand, Czolgosz dropped the handkerchief revealing a pistol. He fired twice. The first bullet bounced off McKinley’s chest. The second ripped through his stomach.

McKinley’s first thoughts were of his wife – “be careful how you tell her, oh be careful” and of his assassin – “be easy with him boys.” He lingered for eight days finally succumbing to gangrene and infection on September 14 with the words “it is God’s way, his will, not ours, be done.” Czolgosz, a self-proclaimed anarchist, had been deeply affected by the treatment of the Slavic miners during the coal strikes of 1897. Justice was swift. His trial began on September 23 and a guilty verdict presented the next day.

Given that the purpose of the exposition where the President was shot was to extol the wonders of electricity, it is one of history’s ironies that his assassin met his maker on October 29, 1901 at Auburn Prison, New York courtesy of the latest method of execution – the electric chair.

|

|

“Suddenly I saw a hand shoved toward the President. . . Then there were two shots in rapid succession.”

Reporter John D. Wells was covering McKinley’s visit to the Exposition and witnessed his assassination. We join his account as the President enters the Temple of Music:

“In the capacity of Exposition representative of the Buffalo Morning Review I was called upon to cover the visit of President McKinley to the Pan-American Exposition on that memorable Friday when the Chief Executive of this great nation was stricken by an assassin. Outside the Temple of Music was a dense crowd, fully fifteen thousand in number, all attracted there by the President’s reception.

Once the President’s party were well inside the building, the doors were closed to allow time to make complete preparations for the levee. The chairs had been peculiarly arranged, leaving a lane from the southeast entrance of the building to the southwest exit, through which the people were to pass. It was scarcely large enough for the passage of more than one file of people. Under the majestic dome of the building, and bordering the passageway, a small space had been cleared. Here the President stood. In line, along each side of the passageway, were the eighteen members of the artillery corps detachment. In company with three other newspaper men, I stood in the rear of the President and to the right of the floral decorations.

|

| The President on his way to the Temple of Music, 15 minutes before being shot. Mrs. McKinley, hidden by her parasol, sits at his side |

When everything had been arranged the signal was given and a guard opened the southeast door. Outside there was a detail of at least twenty Exposition policemen regulating the influx and maintaining the single column. It was exactly at four o’clock. Everybody seemed to be happy, and the President particularly so. He beamed on every one in line and had a kind word for all. Even at this time the assassin must have been within the Temple. I saw him myself but a minute later. Nothing about his person especially attracted me; I just glanced at him, that was all. He appeared to be a kindly disposed German boy, and had a decided Teutonic complexion that could not be mistaken.

The last persons to shake hands with the President were a woman and a little girl, and a negro. I had just consulted my watch, desiring to take the exact time on some little incident that had occurred, and which I do not now recall, for I never recorded the notes. It was exactly 4:07 o’clock. Suddenly I saw a hand shoved toward the President – two of them in fact – as if the person wished to grasp the President’s hand in both his own. In the palm of one hand, the right one, was a handkerchief. Then there were two shots in rapid succession, the interval being so short as to be scarcely measurable.

I stood stockstill. I saw Detective Foster strike upward the hand that would fire the third shot, and then saw a soldier (Private O’Brien of the Artillery Corps, it afterward developed) seize the man from behind and drag him down. Then I saw Gallaher and Ireland jump to the side of Foster, who was then on his knees with his fingers about the throat of the assassin. I took two or three steps toward the President. He had turned about a little and fell into the arms of Detective Geary. Mr. Milburn supported him from the other side. Just a few drops of blood spurted out and dropped on his white waistcoat. I remember this distinctly.

The President was led to a chair a dozen steps away, and into this he sank, exhausted. His collar and necktie were quickly loosed and his shirt opened at the front. I was considerably excited, inasmuch as the shooting appealed to me, to use what may seem to be a heartless expression, in a business way. I was a newspaper man, and there for the sole purpose of covering the story. I might look at it from a sentimental viewpoint later. I did not know which to follow, the President or the assassin. Then I concluded to follow the President. I walked to his side, and, seeing the others using their hats in lieu of fans, did the same with mine. Secretary Cortel who was bending over him, and distinctly I heard the President say: ‘Cortel, you be careful. Tell Mrs. McKinley gently.’

At this juncture I rushed to where the assassin lay prostrate on the floor. A dozen or more men, detectives and guards, were standing over him, striking and kicking him.

|

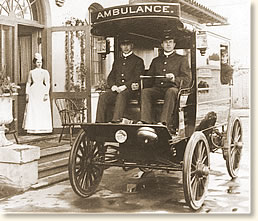

| The ambulance that responded to the call. In keeping with the theme of the Exposition, it was electrically powered. |

I then hastened back to the side of the President’s chair. He had just raised his eyes, and observed the rough treatment being accorded his would-be assassin. Raising his right hand slightly he said: ‘See that no one hurts him.’

Some person with more forethought than others had immediately ordered the doors closed to keep out the crowd. This was done, and the doors were bolted. Outside the immense concourse of people was ignorant of what had happened. There was a murmur of discontent at the closing of the doors. They little imagined that, within, the President was writhing in pain, the victim of an anarchist’s bullet. Not even when the ambulance dashed up to the southwest door of the Temple did they comprehend what had happened – it was so incredible. They thought some woman had fainted and the doors were closed pending her removal. The doctors rushed into the building, and Dr. Ellis felt the pulse. Upon the suggestion of Mr. Milburn, the coat was removed and the President laid on the litter. When the doctors and Mr. Milburn appeared at the door bearing the wounded President a heart-rending sigh went up – such as I have never heard nor ever expect to hear again. Even then the people could scarcely believe that the President had been shot. With the realization of the fact came tears and wailing.

President McKinley, whose popularity was heightened by the victory of the United States in the Spanish-American war, was easily returned to a second term in the election of 1900. His running mate was Theodore Roosevelt, Governor of New York. In less than a year McKinley’s presidency was cut short by an assassin’s bullet delivered in Buffalo, New York. “Now that damned cowboy is in the White House!” declared political boss and Senator from Ohio, Mark Hanna on hearing the news.

|

| President McKinley Reviews Troops, September 6, 1901 |

In September 1901 the President scheduled a visit to the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, NY. Planning for this extravaganza had been in the works for years but postponed during the Spanish-American War. With the war’s conclusion the preparations for the Exposition could go forward and all the governments of the western hemisphere were invited to attend. It occupied 350 acres with buildings whose architecture reflected the style of the Spanish Renaissance. The major theme of the exposition extolled the wonders of the new source of power – electricity.

Arriving on September 6, President McKinley welcomed visitors at the Exposition’s stadium followed by a short reception at the Temple of Music. Noting that the reception was to last only ten minutes, an aide felt the president was unnecessarily exposing himself to danger. In reply, the president commented “No one would wish to hurt me.”

McKinley stood at the head of the reception line in the Temple of Music. His famous handshake whisked each recipient on his way. A slim, 28-year-old man named Leon Czolgosz approached. He had a handkerchief wrapped about his right hand. As the president reached for his left hand, Czolgosz dropped the handkerchief revealing a pistol. He fired twice. The first bullet bounced off McKinley’s chest. The second ripped through his stomach.

McKinley’s first thoughts were of his wife – “be careful how you tell her, oh be careful” and of his assassin – “be easy with him boys.” He lingered for eight days finally succumbing to gangrene and infection on September 14 with the words “it is God’s way, his will, not ours, be done.” Czolgosz, a self-proclaimed anarchist, had been deeply affected by the treatment of the Slavic miners during the coal strikes of 1897. Justice was swift. His trial began on September 23 and a guilty verdict presented the next day.

Given that the purpose of the exposition where the President was shot was to extol the wonders of electricity, it is one of history’s ironies that his assassin met his maker on October 29, 1901 at Auburn Prison, New York courtesy of the latest method of execution – the electric chair.

|

|

Reporter John D. Wells was covering McKinley’s visit to the Exposition and witnessed his assassination. We join his account as the President enters the Temple of Music:

“In the capacity of Exposition representative of the Buffalo Morning Review I was called upon to cover the visit of President McKinley to the Pan-American Exposition on that memorable Friday when the Chief Executive of this great nation was stricken by an assassin. Outside the Temple of Music was a dense crowd, fully fifteen thousand in number, all attracted there by the President’s reception.

Once the President’s party were well inside the building, the doors were closed to allow time to make complete preparations for the levee. The chairs had been peculiarly arranged, leaving a lane from the southeast entrance of the building to the southwest exit, through which the people were to pass. It was scarcely large enough for the passage of more than one file of people. Under the majestic dome of the building, and bordering the passageway, a small space had been cleared. Here the President stood. In line, along each side of the passageway, were the eighteen members of the artillery corps detachment. In company with three other newspaper men, I stood in the rear of the President and to the right of the floral decorations.

|

| The President on his way to the Temple of Music, 15 minutes before being shot. Mrs. McKinley, hidden by her parasol, sits at his side |

When everything had been arranged the signal was given and a guard opened the southeast door. Outside there was a detail of at least twenty Exposition policemen regulating the influx and maintaining the single column. It was exactly at four o’clock. Everybody seemed to be happy, and the President particularly so. He beamed on every one in line and had a kind word for all. Even at this time the assassin must have been within the Temple. I saw him myself but a minute later. Nothing about his person especially attracted me; I just glanced at him, that was all. He appeared to be a kindly disposed German boy, and had a decided Teutonic complexion that could not be mistaken.

The last persons to shake hands with the President were a woman and a little girl, and a negro. I had just consulted my watch, desiring to take the exact time on some little incident that had occurred, and which I do not now recall, for I never recorded the notes. It was exactly 4:07 o’clock. Suddenly I saw a hand shoved toward the President – two of them in fact – as if the person wished to grasp the President’s hand in both his own. In the palm of one hand, the right one, was a handkerchief. Then there were two shots in rapid succession, the interval being so short as to be scarcely measurable.

I stood stockstill. I saw Detective Foster strike upward the hand that would fire the third shot, and then saw a soldier (Private O’Brien of the Artillery Corps, it afterward developed) seize the man from behind and drag him down. Then I saw Gallaher and Ireland jump to the side of Foster, who was then on his knees with his fingers about the throat of the assassin. I took two or three steps toward the President. He had turned about a little and fell into the arms of Detective Geary. Mr. Milburn supported him from the other side. Just a few drops of blood spurted out and dropped on his white waistcoat. I remember this distinctly.

The President was led to a chair a dozen steps away, and into this he sank, exhausted. His collar and necktie were quickly loosed and his shirt opened at the front. I was considerably excited, inasmuch as the shooting appealed to me, to use what may seem to be a heartless expression, in a business way. I was a newspaper man, and there for the sole purpose of covering the story. I might look at it from a sentimental viewpoint later. I did not know which to follow, the President or the assassin. Then I concluded to follow the President. I walked to his side, and, seeing the others using their hats in lieu of fans, did the same with mine. Secretary Cortel who was bending over him, and distinctly I heard the President say: ‘Cortel, you be careful. Tell Mrs. McKinley gently.’

At this juncture I rushed to where the assassin lay prostrate on the floor. A dozen or more men, detectives and guards, were standing over him, striking and kicking him.

|

| The ambulance that responded to the call. In keeping with the theme of the Exposition, it was electrically powered. |

I then hastened back to the side of the President’s chair. He had just raised his eyes, and observed the rough treatment being accorded his would-be assassin. Raising his right hand slightly he said: ‘See that no one hurts him.’

Some person with more forethought than others had immediately ordered the doors closed to keep out the crowd. This was done, and the doors were bolted. Outside the immense concourse of people was ignorant of what had happened. There was a murmur of discontent at the closing of the doors. They little imagined that, within, the President was writhing in pain, the victim of an anarchist’s bullet. Not even when the ambulance dashed up to the southwest door of the Temple did they comprehend what had happened – it was so incredible. They thought some woman had fainted and the doors were closed pending her removal. The doctors rushed into the building, and Dr. Ellis felt the pulse. Upon the suggestion of Mr. Milburn, the coat was removed and the President laid on the litter. When the doctors and Mr. Milburn appeared at the door bearing the wounded President a heart-rending sigh went up – such as I have never heard nor ever expect to hear again. Even then the people could scarcely believe that the President had been shot. With the realization of the fact came tears and wailing.

Source: Eyewitness to History

Comment |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Tweet

Tweet

Add My Story

Add My Story