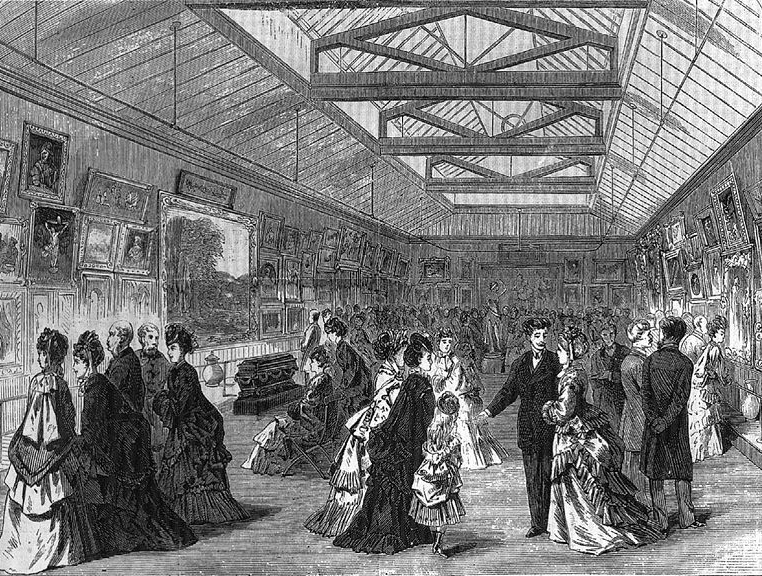

The Art Committee of the Union League Club held a meeting led by William Cullen Bryant to discuss the creation of The New York City Metropolitan Museum of Art on November 23, 1869, in the Theatre of the Club on Twenty-sixth Street. Invitations were sent to the members of the Union League Club, the National Academy of Design and other artists, the Institute of Architects, the New York Historical Society, the Century, Manhattan, and other clubs.

We are assembled, my friends, to consider the subject of founding in this city a Museum of Art, a repository of the productions of artists of every class, which shall be in some measure worthy of this great metropolis and of the wide empire of which New York is the commercial center. I understand that no rivalry with any other project is contemplated, no competition, save with similar institutions in other countries, and then only such modest competition as a Museum in its infancy may aspire to hold with those which were founded centuries ago, and are enriched with the additions made by the munificence of successive generations. No precise method of reaching this result has been determined on, but the object of the present meeting is to awaken the public, so far as such a meeting can influence the general mind, to the importance of taking early and effectual measures for founding such a museum as I have described.

Our city is the third great city of the civilized world. Our republic has already taken its place among the great powers of the earth; it is great in extent, great in population, great in the activity and enterprise of her people. It is the richest nation in the world, if paying off an enormous national debt with a rapidity unexampled in history be any proof of riches; the richest in the world, if contented submission to heavy taxation be a sign of wealth; the richest in the world, if quietly to allow itself to be annually plundered of immense sums by men who seek public stations for their individual profit be a token of public prosperity. My friends, if a tenth part of what is every year stolen from us in this way, in the city where we live, under pretence of the public service, and poured profusely into the coffers of political rogues, were expended on a Museum of Art, we might have, reposited in spacious and stately buildings, collections formed of works left by the world’s greatest artists, which would be the pride of our country. We might have an annual revenue which would bring to the Museum every stray statue and picture of merit for which there should be no ready sale to individuals, every smaller collection in the country which its owner could no longer conveniently keep, every noble work by the artists of former ages, which by any casualty, after long remaining on the walls of some ancient building, should be again thrown upon the world.

But what have we done — numerous as our people are, and so rich as to be contentedly cheated and plundered, what have we done toward founding such a repository? We have hardly made a step toward it. Yet, beyond the sea there is the little kingdom of Saxony, which, with an area less than that of Massachusetts, and a population but little larger, possesses a Museum of the Fine Arts marvellously rich, which no man who visits the continent of Europe is willing to own that he has not seen. There is Spain, a third-rate power of Europe and poor besides, with a Museum of Fine Arts at her capital, the opulence and extent of which absolutely bewilder the visitor. I will not speak of France or of England, conquering nations, which have gathered their treasures of art in part from regions overrun by their armies; nor yet of Italy, the fortunate inheritor of so many glorious productions of her own artists. But there are Holland and Belgium, kingdoms almost too small to be heeded by the greater powers of Europe in the consultations which decide the destinies of nations, and these little kingdoms have their public collections of art, the resort of admiring visitors from all parts of the civilized world.

But in our country, when the owner of a private gallery of art desires to leave his treasures where they can be seen by the public, he looks in vain for any institution to which he can send them. A public-spirited citizen desires to employ a favorite artist upon some great historical picture; here are no walls on which it can hang in the public sight. A large collection of works of art, made at great cost, and with great pains, gathered perhaps during a life-time, is for sale in Europe. We may find here men willing to contribute to purchase it, but if it should be brought to our country there is no edifice here to give it hospitality.

In 1857, during a visit to Spain, I found in Madrid a rich private collection of pictures, made by Medraza, an aged painter, during a long life, and at a period when frequent social and political changes in that country dismantled many palaces of the old nobility of the works of art which adorned them. In that collection were many pictures by the illustrious elder artists of Italy, Spain, and Holland. The whole might have been bought for half its value, but if it had been brought over to our country, we had no gallery to hold it. The same year I stood in the famous Campana Collection of marbles, at Rome, which was then waiting for a purchaser – a noble collection, busts and statues of the ancient philosophers, orators, and poets, the majestic forms of Roman senators, the deities of ancient mythology, ‘The fair humanities of old religion,’ but if they had been purchased by our countrymen and landed here, we should have been obliged to leave them in boxes, just as they were packed.

Moreover, we require an extensive public gallery to contain the greater works of our painters and sculptors. The American soil is prolific of artists. The fine arts blossom not only in the populous regions of our country, but even in its solitary places. Go where you will, into whatever museum of art in the old world, you will find there artists from the new, contemplating or copying the masterpieces of art which they contain. Our artists swarm in Italy. When I was last at Rome, two years since, I found the number of American artists residing there as two to one compared with those from the British isles. But there are beginners among us who have not the means of resorting to distant countries for that instruction in art which is derived from carefully studying works of acknowledged excellence. For these a gallery is needed at home, which shall vie with those abroad, if not in the multitude, yet in the merit, of the works it contains.

Yet further, it is unfortunate for our artists, our painters especially, that they too often find their genius cramped by the narrow space in which it is constrained to exert itself. It is like a bird in a cage which can only take short flights from one perch to another and longs to stretch its wings in an ampler atmosphere. Producing works for private dwellings, our painters are for the most part obliged to confine themselves to cabinet pictures, and have little opportunity for that larger treatment of important subjects which a greater breadth of canvas would allow them and by which the higher and nobler triumphs of their art have been achieved.

There is yet another view of the subject, and a most important one. When I consider, my friends, the prospect which opens before this great mart of the western world, 1 am moved by feelings which I feel it somewhat difficult to clearly define. The growth of our city is already wonderfully rapid; it is every day spreading itself into the surrounding region, and overwhelming it like an inundation. Now that our great railway has been laid from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Eastern Asia and Western Europe will shake hands over our republic. New York will be the mart from which Europe will receive a large proportion of the products of China, and will become not only a center of commerce for the New World, but for that region which is to Europe the most remote part of the Old. A new impulse will be given to the growth of our city, which I cannot contemplate without an emotion akin to dismay. Men will flock in greater numbers than ever before to plant themselves on a spot so favorable to the exchange of commodities between distant regions; and here will be an aggregation of human life, a concentration of all that ennobles and all that degrades humanity, on a scale which the imagination cannot venture to measure. To great cities resort not only all that is eminent in talent, all that is splendid in genius, and all that is active in philanthropy; but also all that is most dexterous in villany, and all that is most foul in guilt. It is in the labyrinths of such mighty and crowded populations that crime finds its safest lurking-places; it is there that vice spreads its most seductive and fatal snares, and sin is pampered and festers and spreads its contagion in the greatest security.

My friends, it is important that we should encounter the temptations to vice in this great and too rapidly growing capital by attractive entertainments of an innocent and improving character. We have libraries and reading-rooms, and this is well ; we have also spacious halls for musical entertainments, and that also is well; but there are times when we do not care to read and are satiate with listening to sweet sounds, and when we more willingly contemplate works of art. It is the business of the true philanthropist to find means of gratifying this preference. We must be beforehand with vice in our arrangements for all that gives grace and cheerfulness to society. The influence of works of art is wholesome, ennobling, instructive. Besides the cultivation of the sense of beauty – - in other words, the perception of order, symmetry, proportion of parts, which is of near kindred to the moral sentiments – the intelligent contemplation of a great gallery of works of art is a lesson in history, a lesson in biography, a lesson in the antiquities of different countries. Half our knowledge of the customs and modes of life among the ancient Greeks and Romans is derived from the remains of ancient art.

Let it be remembered to the honor of art that if it has ever been perverted to the purpose of vice.it has only been at the bidding of some corrupt court or at the desire of some opulent and powerful voluptuary whose word was law. When intended for the general eye no such stain rests on the works of art. Let me close with an anecdote of the influence of a well-known work. I was once speaking to the poet Rogers in commendation of the painting of Ary Scheffer, entitled Christ the Consoler. ‘I have an engraving of it,’ he answered, ‘hanging at my bedside, where it meets my eye every morning.’ The aged poet, over whom already impended the shadow that shrouds the entrance to the next world, found his morning meditations guided by that work to the Founder of our religion.

To read more about the Metropolitan Museum of Art and it’s opening on April 13, 1870 visit The Internet Archive’s website.

Comment |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Tweet

Tweet

Add My Story

Add My Story