On July 14, 1789, the U.S. Ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson, was a witness to the events of a day in Paris that is commonly associated with the beginning of the French Revolution. Jefferson recorded the events of the day in a lengthy and detailed letter to John Jay, then Secretary of Foreign Affairs

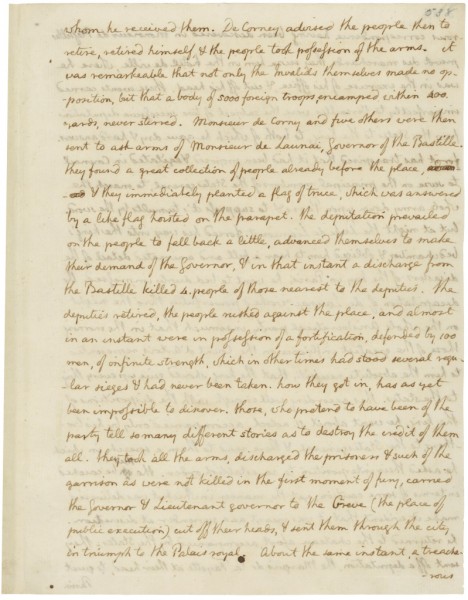

Letter from Jefferson to Jay, July 19, 1789. National Archives, Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention:

On July 14th [afternoon]. Monsieur de Corny [a member of the States General] and five others were… sent to ask arms of Monsieur de Launay, Governor of the Bastille. They found a great collection of people already before the place, and they immediately planted a flag of truce, which was answered by a like flag hoisted on the parapet. The deputation prevailed on the people to fall back a little, advanced themselves to make their demand of the Governor, and in that instant a discharge from the Bastille killed 4. people of those nearest to the deputies. The deputies retired, the people rushed against the place, and almost in an instant were in possession of a fortification, defended by 100 men, of infinite strength, which in other times had stood several regular sieges and had never been taken. How they got in, has as yet been impossible to discover. Those, who pretend to have been of the party tell so many different stories as to destroy the credit of them all. They took all the arms, discharged the prisoners and such of the garrison as were not killed in the first moment of fury, carried the Governor and Lieutenant governor to the Greve (the place of public execution) cut off their heads, and set them through the city in triumph to the Palais royal.

But at night the Duke de Liancourt forced his way into the king’s bedchamber, and obliged him to hear a full and animated detail of the disasters of the day in Paris. [The King] went to bed deeply impressed… the king…went about 11. oclock, accompanied only by his brothers, to the States general, and there read to them a speech, in which he asked their interposition to re-establish order. Tho this be couched in terms of some caution, yet the manner in which it was delivered made it evident that it was meant as a surrender at discretion. He returned to the chateau afoot, accompanied by the States. They sent off a deputation, the Marquis de la Fayette at their head, to quiet Paris. He had the same morning been named Commandant en chef of the milice Bourgeoise [the King’s Militia], …A body of the Swiss guards, of the regiment of Ventimille [Italy], and the city horse guards join the people.

The alarm at Versailles increases instead of abating. They believed that the Aristocrats of Paris were under pillage and carnage, that 150,000 men were in arms coming to Versailles to massacre the Royal family, the court, the ministers and all connected with them, their practices and principles.The Aristocrats of the Nobles and Clergy in the States general vied with each other in declaring how sincerely they were converted to the justice of voting by persons, and how determined to go with the nation…

The king came to Paris, leaving the queen in consternation for his return. Omitting the less important figures of the procession, I will only observe that the king’s carriage was in the center, on each side of it the States general, in two ranks, afoot, at their head the Marquis de la Fayette as commander in chief, on horseback, and Bourgeois guards before and behind. About 60,000 citizens of all forms and colours, armed with the muskets of the Bastille and Invalids as far as they would go, the rest with pistols, swords, pikes, pruning hooks, scythes &c. lined all the streets thro’ which the procession passed, and, with the crowds of people in the streets, doors and windows, saluted them every where with cries of ‘vive la nation.’ But not a single ‘vive le roy’ was heard.

The king landed at the Hotel de ville [City of Hall in Paris]. There Monsieur Bailly [Mayor of Paris] presented and put into his hat the popular cockade, and addressed him. The king being unprepared and unable to answer, Bailly went to him, gathered from him some scraps of sentences, and made out an answer, which he delivered to the Audience as from the king. On their return the popular cries were ‘vive le roy et la nation.’ He was conducted by a garde Bourgeoise [militia] to his palace at Versailles, and thus concluded such an Amende honorable as no sovereign ever made, and no people ever received.

After observing the French revolution in person for another six weeks and only three weeks before departing Paris for his beloved Virginia, Jefferson wrote:

I say, the earth belongs to each of these generations during its course, fully and in its own right. The second generation receives it clear of the debts and incumbrances of the first, the third of the second, and so on. For if the first could charge it with a debt, then the earth would belong to the dead and not to the living generation. Then, no generation can contract debts greater than may be paid during the course of its own existence. Letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 6, 1789.

Comment |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Tweet

Tweet

Add My Story

Add My Story