Author: Ben Nussbaum

The March on Washington in 1963 has become identified with Martin Luther King, Jr., who delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech in front of a quarter of a million people gathered on the National Mall.

But as the March was being organized, King was just one piece of the puzzle. The March had 10 chairmen, including King but also representatives from other civil rights and religious groups, as well as the head of the United Automobile Workers (UAW).

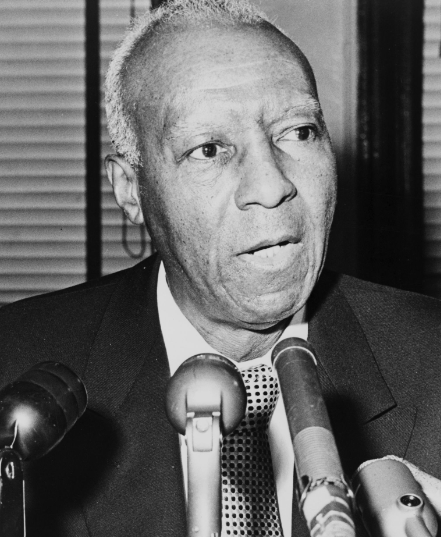

Six of the ten chairmen were African American. This group came to be known as the Big Six. In addition to King, it included the leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League, as well as the heads of two new, activist civil rights, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The man who led the Big Six wasn’t King. It was A. Philip Randolph.

Randolph was a leftist union organizer; he twice ran for office in New York as a socialist. In 1925 he was elected president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a position he held until 1968. As head of the Sleeping Car Porters, Randolph became one of the best known African Americans in the country.

This raises a couple obvious questions: What are sleeping car porters and why was the head of their union so powerful?

The answer starts with a man named George Pullman, who developed the concept of a luxurious sleeping car that could be attached to existing trains. The Pullman company quickly became a household name; the cars it made were called Pullman cars. The Pullman company was also known for viciously breaking a bitter, protracted strike in 1894. That strike grew to involve 250,000 workers across the country. Thirty-four strikers were killed in the violence spawned by the strike, and it remains a defining moment in the history of American labor unions.

The Pullman Company continued to grow after breaking the strike. By 1925, 12,000 porters were employed by Pullman. These porters, who attended to the needs of the customers in the Pullman cars, formed the membership of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. They were all men. And they were all black.

Being a porter was glamorous. The job paid well. On account of their travel and contact with other porters, the Pullman men became an important pathway of information among African Americans. In an era when African Americans had few jobs opportunities, the Pullman porters were stars.

So when the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters actually succeeded in signing a collective bargaining agreement with the Pullman Company in 1937, it was major event both because of Pullman’s famous strike-breaking history and the prominence the porters had in the African American community. The collective bargaining agreement launched the porters’ president, A. Philip Randolph, to fame.

By the time of the March on Washington in 1963, the railroads had already lost much of their power and the membership in Randolph’s union had dwindled. But it’s a testimony to the power of the porters that the man who led the March still proudly identified himself, first and foremost, as their president.

Comment |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Tweet

Tweet

Add My Story

Add My Story