In 1666, London was England’s economic powerhouse with an estimated population of 500,000. Its closest rival in size was Bristol with a population of only 30,000.

The city’s architecture had changed little from the Middle Ages. Narrow, cobble-stoned, foul-smelling streets doubled as the city’s sewers. Many of the streets were lined with homes made of wood and pitch, some four stories high. The upper stories of these homes overhung the lower ones and projected into the street, effectively blocking the sun and decreasing the distance between the buildings. This typical construction and London’s uncontrolled growth had created a fireman’s nightmare: a city dominated by old, dry, wooden structures, tightly packed into a confined space just waiting for a spark to ignite disaster.

The nightmare became reality in the early morning hours of September 2, 1666 when a small fire erupted in the shop of the King’s baker. Flames fanned by a steady wind quickly spread to the surrounding neighborhood. By 8 o’clock in the morning the fire had reached the Thames and progressed half way across London Bridge, its advance halted only by a gap in the shops on the bridge.

Elsewhere, the conflagration raged uncontrollably, consuming all in its path for three days. Fire fighters resorted to blowing up buildings with gunpowder in order to deny the inferno its fuel. This, plus the subsiding of the winds, reduced the fire so that it could be extinguished – but not before it gave one last gasp that threatened Westminster.

Thankfully, the loss of life was low, but approximately four fifths of the city had been destroyed. The cataclysm did have some positive outcomes. From the fire’s ashes arose a new, better planned city, with wider streets and buildings made of fire-resistant stone. Destroyed by the fire, St. Paul’s Cathedral was rebuilt along with 49 other churches. Additionally, the rats that harbored the plague-infected fleas that had devastated the city the previous year were consumed by the flames

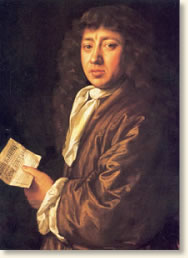

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703)

He started life as a poor East London tailor’s son but he became an important man who helped to look after the king’s ships. We know a lot about him because he kept a diary describing his life. In 1666 when the great fire broke out, he was living with his wife in Seething Lane, near the Tower of London. His diary gives a vivid account of the disaster.

This is how he describes the scene on the first day of the fire:

“All over the Thames with your face in the wind you were almost burned by the shower of fire drops. We went to a little alehouse and saw the fire grow. As it grew darker, it seemed more and more, in corners and on steeples, between churches and houses, as far as we could see, in a most horrid, spiteful, blood-red flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire. We stayed till we saw the fire as one whole arch of flame, from one side of the bridge to the other. Churches, houses and all were on fire, all flaming at once, with a horrid noise the flames made and the cracking of the houses in their ruin.”

|

| The Great Fire ravages London |

Pepys lives near the Tower of London and we join his story during the early hours of a Sunday morning when he is awakened by a servant spreading the alarm of a fire:

“September 2

Lords day. Some of our maids sitting up late last night to get things ready against our feast today, Jane called us up, about 3 in the morning, to tell us of a great fire they saw in the City.

So I rose, and slipped on my nightgown and went to her window, and thought it to be on the back side of Markelane at the furthest; but being unused to such fires as followed, I thought it far enough off, and so went to bed again and to sleep.

About 7 rose again to dress myself, and there looked out at the window and saw the fire not so much as it was, and further off. So to my closet to set things to rights after yesterday’s cleaning.

By and by Jane comes and tells me that she hears that above 300 houses have been burned down tonight by the fire we saw, and that it was now burning down all Fish Street by London Bridge. So I made myself ready presently, and walked to the Tower and there got up upon one of the high places, Sir J. Robinson’s little son going up with me; and there I did see the houses at that end of the bridge all on fire, and an infinite great fire on this and the other side of the bridge.

So down, with my heart full of trouble, to the Lieutenant of the Tower, who tells me that it begun this morning in the King’s baker’s house in Pudding Lane, and that it hath burned down St. Magnes Church and most part of Fish Street already.

|

| Samuel Pepys |

So I down to the water-side and there got a boat and through bridge, and there saw a lamentable fire. Poor Michells house, as far as the Old Swan, already burned that way and the fire running further, that in a very little time it got as far as the Stillyard while I was there.

Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the River or bringing them into lighters that lay off. Poor people staying in their houses as long as the very fire touched them, and then running into boats or clambering from one pair of stair by the water-side to another.”

“He cried like a fainting woman”

Pepys takes a boat to Whitehall where he is summoned by the King to report on what he has seen. Pepys recommends that houses in the fire’s path be pulled down to squelch the blaze. The King orders him to find the Lord Mayor and implement this strategy. We pick up Pepys’ story as he takes a carriage to St. Paul’s to find the Lord Mayor:

“…walked along Watling Street as well as I could, every creature coming away loaden with goods to save – and here and there sick people carried away in beds.

At last met my Lord Mayor like a man spent, with a handkerchief about his neck. To the King’s message, he cried like a fainting woman, ‘Lord what can I do? I am spent. People will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses. But the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it.’ “

Pepys leaves the Lord Mayor and begins to walk home:

“…seeing the people all almost distracted and no means used to quench the fire. The houses too, so very thick thereabouts, and full of matter for burning, as pitch and tar, in Thames Street – and warehouses of oil and wines and brandy and other things.

Here I saw Mr. Isaccke Houblon, that handsome man – prettily dressed and dirty at his door at Dowgate, receiving some of his brother’s things whose houses were on fire; and as he says have been removed twice already, and he doubts (as it soon proved) that they must be in a little time removed from his house also. And to see the churches all filling with goods, by people who themselves should have been quietly there at this time.”

“It made me weep to see it.”

By this time it is about noon and Pepys returns to his home to get something to eat. His meal completed, the diarist returns to the streets making his way to the Thames where he hires a boat. We join his story as he travels up the river:

“…all over the Thames, with one’s face in the wind you were almost burned with a shower of Firedrops – this is very true – so as houses were burned by these drops and flakes of fire, three or four, nay five or six houses, one from another. When we could endure no more upon the water, we to a little alehouse on the Bankside over against the Three Cranes, and there stayed till it was dark almost and saw the fire grow; and as it grow darker, appeared more and more, and, in Corners and upon steeples and between churches and houses, as far as we could see up the hill of the city, in a most horrid malicious bloody flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire.

We stayed till, it being darkish, we saw the fire as only one entire arch of fire from this to the other side of the bridge, and in a bow up the hill, for an arch of above a mile long. It made me weep to see it. The churches, houses, and all on fire and flaming at once, and a horrid noise the flames made, and the cracking of houses at their ruin.

So home with a sad heart, and there find everybody discoursing and lamenting the fire; and poor Tom Hater came with some few of his goods saved out of his house, which is burned upon Fish-street hill., I invited him to lie at my house, and did receive his goods: but was deceived in his lying there, the noise coming every moment of the growth of the Fire, so as we were forced to begin to pack a up our own goods and prepare for their removal. And did by moonshine (it being brave, dry, and moonshine and warm weather) carry much of my goods into the garden, and Mr. Hater and I did remove my money and Iron-chests into my cellar – as thinking that the safest place. And got my bags of gold into my office ready to carry away…”

The Escape

“September 3

About 4 a-clock in the morning, my Lady Batten sent me a cart to carry away all my money and plate and best things to Sir W Riders at Bednall greene; which I did, riding myself in my nightgown in the cart; and Lord, to see how the streets and the highways are crowded with people, running and riding and getting of carts at any rate to fetch away things.”

Source: Eyewitness to History

Comment |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook

Tweet

Tweet

Add My Story

Add My Story